Combined liver-kidney transplant in children

Clare Lindner1, Amber Kazi 2, Jodi Smith2, Sharon Bartosh3, Juhi Kumar4, Chloe Douglas5, Lyndsay Harshman6, Sarah Kizilbash7, Rachel Engen3.

1Pediatric Nephrology, University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , United States; 2Pediatric Nephrology, Seattle Children's, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States; 3Pediatric Nephrology, University of Madison , Madison , WI, United States; 4Pediatric Nephrology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States; 5Pediatric Nephrology, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR, United States; 6Pediatric Nephrology, University of Iowa, Iowa City , IA, United States; 7Pediatric Nephrology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Background: Pediatric combined liver-kidney transplant (CLKT) can be a lifesaving and life-improving procedure for children with rare diseases such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, primary hyperoxaluria type 1, and certain metabolic conditions. Guidelines and consensus statements for pediatric multi-organ transplantation are lacking. Data on patient and transplant characteristics as well as management and outcomes of this small but vulnerable population are limited.

Methods: Retrospective cohort study of pediatric CLKT, liver-alone (LT), and kidney-alone transplants (KT) in the United States from January 1st, 2001 to December 31st, 2019 in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Primary outcomes of interest included allograft and patient survival.

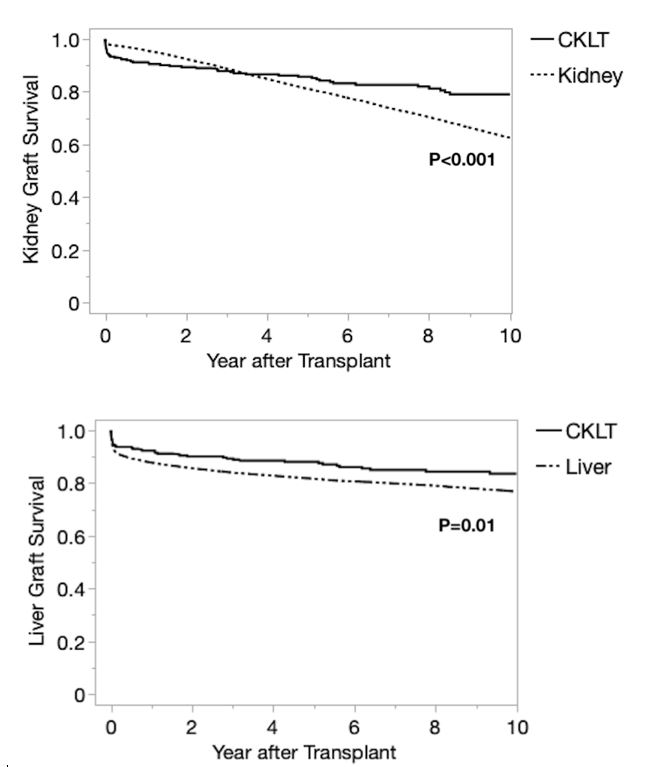

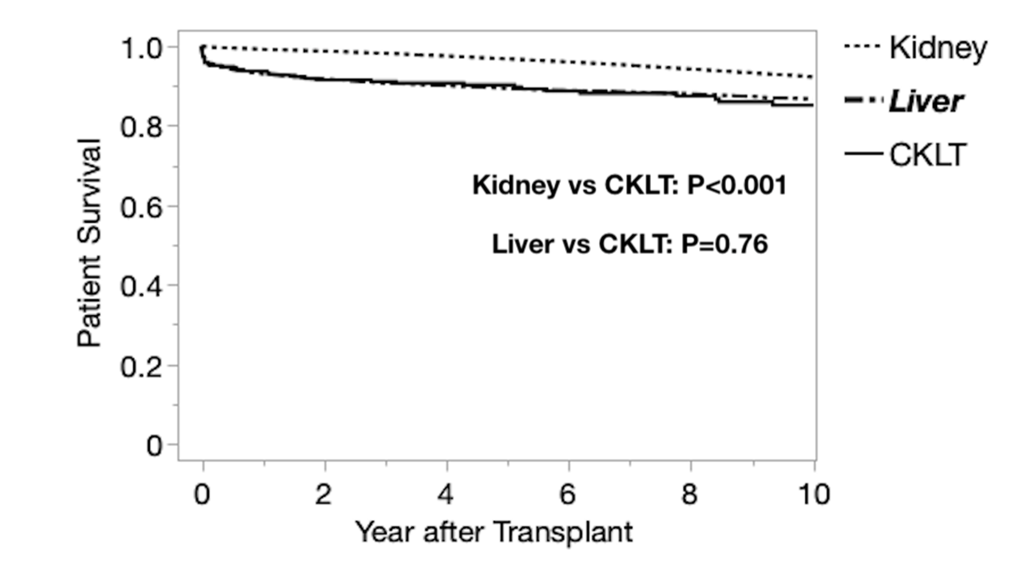

Results: There were 284 CLKT recipients during the study period. Median age was 10 years; 22.5% had polycystic kidney disease and 18.7% had primary hyperoxaluria. Compared to LT and KT, CLKT recipients were more likely to have a history of prior transplant (12% prior kidney, 6.7% prior liver), be listed at multiple centers and receive dialysis prior to CLKT. CLKT recipients were more likely to be listed with exception status, were transplanted with lower MELD/PELD scores, and were less likely to receive a partial liver, compared to LT. CLKT recipients also had higher incidence of en bloc kidney transplants, KDPI 35-85% donor kidneys, and delayed graft function (DGF) compared to KT. One year graft survival rates for CLKT were superior to LT but inferior to KT. Longer term (5 and 10 year) kidney allograft survival was higher for CLKT recipients compared to KT, despite worse HLA matching. CLKT patient survival was inferior to KT but similar to LT.

Conclusion: CLKT is a rare procedure that results in similar short-term outcomes to KT and LT alone, despite a complex patient population. CLKT recipients differ by demographics, primary disease, KDPI, ABDR mismatch, and delayed graft function compared to KT or LT. CLKT recipients have higher long-term allograft survival rates beginning at 2 years. CLKT patient mortality is similar to that of LT recipients. However, the lower patient survival of CLKT relative to KT alone suggests that this procedure should be limited to those with a clear and present need for liver transplantation. Further research is needed to define the appropriate threshold for CLKT and determine best practices to manage patient, liver allograft, and kidney allograft survival in this population.

[1] kidney transplant

[2] liver transplant